A quasi-literary blog: book reviews in modern and classic fiction, occasional original stories and frequent pontification. Come on in.

- For Whom the Bell Tolls

Friday, 31 December 2010

The Pilgrim's Tale

Sunday, 26 December 2010

As I Lay Reading

Saturday, 18 December 2010

Danger on the Edge of Town

Sunday, 12 December 2010

Kings and Fools

I have returned to Anthony Burgess, with his novel Any Old Iron, which follows the remarkable Jones family throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The old iron of the title is Excalibur, a.k.a. the Sword of Mars, once wielded by Attila the Hun before ending up in the hands of King Arthur, according to popular legend.

For a story ostensibly about Excalibur, the first major surprise is how little the sword itself features. It does, however, hang over the fates of the various members of the Jones family, and by charting their fortunes Burgess is able to cover an extraordinary variety of subject matter. The sinking of the Titanic, the Russian revolution, two World Wars, the struggle for Welsh independence, and the founding of the nascent State of Israel are all effortlessly and mercilessly scrutinised.

When Burgess writes about the Second World War, his acerbic wit is reminiscent of Joseph Heller. One Private Jones suffers so many bouts of bronchitis, pneumonia, and minor war-related injuries that, despite serving his country for several years, he never actually sees any fighting. There is a powerful sense of the absurdity of war. Another Jones, defending his classical education as a means to interpret the mad situation around him, reduces war and Homeric verse to the level of crapulent nightmares, concluding that “We’re all living in the aftermath of a cheese supper.”

Burgess’ view of Welsh independence and Zionism are just as jaundiced. The two struggling states are set up as parallels, with the bumbling Welsh independence movement robbing post offices and giving old ladies heart attacks. Perhaps because it is still a delicate political issue, perhaps because Wales is more integral to the plot, Israel is seen as a distant absurdity, used by the Welsh freedom fighters as an example of what could be achieved. This absurdity is brought out by discussions of the ethnic similarities between the two groups, and the suggestion that the Welsh are a fragment of the Jewish diaspora.

So, where does Excalibur fit in? Having been looted by the Nazis and captured by the Soviets it resides in a Russian museum. There Reg Jones, half mad with his love for a Russian woman and his fear that she will be sent to the Siberian work camps, liberates it from the icy grasp of the Soviets. He does so with no nationalistic intent, his wartime experiences having destroyed any such naive ideals. But when he returns it to Wales, and when the Luftwaffe unintentionally expose some apparently Arthurian ruins, the nationalistic fervour of others is whipped up. For Reg, the end of the war is sadly not the end of pointless quarrelling.

Clearly, for Burgess, the absurdity of war is inseparable from the absurdity of nation-building. Thousands of Russians were worked to death in Stalin’s USSR because they had been exposed to the decadence of Western society, and could have spread word of its success. Welsh nationalism seems the nostalgic province of petty thugs. Wars, and the thought of dying for one’s country, are absurd.

Any Old Iron tumbles majestically and mockingly through the terrible events of the twentieth century. The Sword of Arthur almost seems like an afterthought, until you look closely and realise that it symbolises all the nostalgia for conquests and golden ages that motivated so much of the bloodshed in our recent history. It is a rusty relic, quite out of place in the modern world.

Sunday, 5 December 2010

Come out to play...

The front cover of Sol Yurick’s The Warriors bombastically proclaims that it is the most dangerous book since A Clockwork Orange. It is not. Yes, there are ritualised stabbings, gang-rapings and casual violence aplenty, but the comparison was clearly made by the sales team rather than the critics.

I read The Warriors because of the movie of the same name, which is something of an 80s cult classic, all urban decay and hipster slang. The same two features dominate the book, but whereas in Paramount’s version the hero and the tart-with-a-heart get together, in Yurick’s original she is raped and left in an alleyway beside a bleeding corpse. Predictably, the Warriors have been neutered for Hollywood.

The bombast of the front cover sets the tone for the whole novel. It follows a gang, the Coney Island Dominators, in a not-too-distant New York future, as they make their way home through fifteen miles of hostile territory after a huge peace talk between all the NY gangs ended in anarchy. The young men of the gangs are obsessed with their machismo, their appearance, their ‘rep’. If you look at them the wrong way, they’ll bop you. Or jap you. Or waste you.

While one or two scenes make for slightly uncomfortable reading, there is certainly nothing as distressing as Anthony Burgess’ wilder moments. The most uncomfortable aspect for me was the narrator’s – perhaps the author’s – tacit assumption that the female victims of the Dominators nocturnal activities were a) asking for it, and b) enjoyed it. The book was written in the eighties. Whether it was behind the times then and seems even more so now, or whether the author is attempting to be provocative, is difficult to tell.

What the novel does do well is evoke the sweat and seediness of a hot New York night. I’ve never been, but I have experienced enough American culture and been through the arse-ends of enough big cities to find it convincing. All the talk of fairies, fags and whores is reminiscent of Travis’ skewed view of the nightlife in Taxi Driver, while the sweaty, paranoid road trip aspect reminded me of Kerouac’s On the Road.

The Warriors is not a sophisticated work of literature. I read it in about three hours flat. But given how much I enjoy the film, and how many times I’ve seen it, I was impressed that the book wasn’t a disappointing experience. Yurick’s prose is nothing special, but it isn’t actively bad, which is what I’d been bracing myself for following some friendly warnings. And for a novel unashamedly based on gang violence, it does at least voice some intelligent thoughts. One character’s aspiration is to earn a fearsome ‘rep’ and make others follow his orders by sitting behind a desk and working hard, by having a big house, a nice car, a pretty wife. There’s that latent misogyny again, but at least these are reasonably honest aspirations.

The real tragedy is that by the end of the book, the one character that has developed the most, who conquered his inadequacies in a ten-cent arcade shoot-out game against a shinily handsome plastic sheriff, is back where he started. His home is his prison, and his potential as a leader of men and as an honest person seems likely to remain unfulfilled.

Tuesday, 30 November 2010

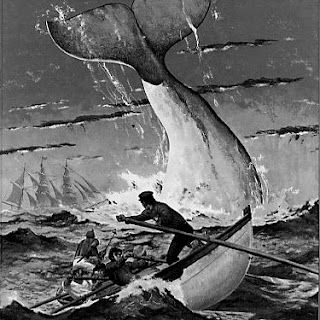

Ahab's Philosophy

But the utmost proof I can provide is stored deep within you, though you know it not. Every shred, every tatter of self-loathing, of humiliation, of despair redounds to the curses of your creator. Man is not an instantaneous, unspawned hater of others, but was made in the image of another. Life is not so bleak! We are not without precedent, alone in this world; our actions are validated and confirmed by the actions of our maker. Not for nothing were we made weak, and jealous and wrathful, and not for nothing does everyman seek to improve his lot by shedding the blood of his neighbour.

But the utmost proof I can provide is stored deep within you, though you know it not. Every shred, every tatter of self-loathing, of humiliation, of despair redounds to the curses of your creator. Man is not an instantaneous, unspawned hater of others, but was made in the image of another. Life is not so bleak! We are not without precedent, alone in this world; our actions are validated and confirmed by the actions of our maker. Not for nothing were we made weak, and jealous and wrathful, and not for nothing does everyman seek to improve his lot by shedding the blood of his neighbour.Tuesday, 23 November 2010

Melville and I

Thursday, 18 November 2010

A Hand-Made Tale

Friday, 12 November 2010

Autopeotomy and the OED

A brief foray into non-fiction.

Simon Winchester’s The Surgeon of Crowthorne is the history of a former US army surgeon imprisoned in Broadmoor lunatic asylum, near Crowthorne, in the late nineteenth century. It charts his involvement with the creation of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, which was compiled with the help of hundreds of volunteers throughout the English-speaking world who read obscure books and sent in little slips of paper with words and quotations illustrating their meanings. The surgeon, Dr Minor, was imprisoned after he killed a man in Lambeth whilst suffering from one of his periodic, almost nightly, bouts of delusion. From his asylum cell, lined with his many books, he begins a correspondence with the editor of the OED that will last twenty years and will prove him to be one of the most meticulous and productive of the many volunteers involved in the project.

The subject matter, a murder in smoggy Victorian London and the severe conditions of a nineteenth-century lunatic asylum, are enough to make Edgar Allen Poe salivate. The story hinges on the tension between Minor’s insanity – he is convinced that he endures nightly persecution by would-be assassins who emerge from the floorboards to drug, torture and sexually abuse him – and the evident lucidity of his work on the dictionary. It is told well, with a verbosity that suits the bookish subject matter, and leaves one’s own vocabulary enhanced (see title, a late twist in Dr Minor’s already grim saga).

As with all such books – and to continue on from the previous post on Burgess – it suffers from what I perceive to be a problem. Some of the facts are clearly verifiable, and the author acknowledges his debts to many documents, institutional registers and the like. But some are obviously the product of artistic license, and this bothers me. Either write a history, or write a novel. I might sound a bit militant here, but I am a historian by training. On the back of the book, it is described as a ‘classic work of detection’. Very noncommittal. But Winchester does intersperse his narrative with enough perhapses and maybes to let us know that he is filling in a number of gaps. He is being honest, at least.

I sound very snobbish about this, I know. I enjoy a book that meddles with the line between fiction and reality, but I think I only enjoy this in a fictional context. Hopefully somewhere out there is a semi-history or a historical novel that can persuade me to take the plunge off my high horse, but I’m not quite there yet.

Tuesday, 9 November 2010

Beyond Nadsat

Saturday, 6 November 2010

Once More With Feeling

Thursday, 28 October 2010

Big City, Deep Time

I’ve finished The Book of Dave and it has been one of the most intense and enthralling novels I’ve read for a long time.

At one point, Self uses the phrase ‘deep time’, and this is the book’s real appeal for me. It is soaked in time and place, and the two are irrevocably linked. The past is heard through Dave’s recollections of stories told by his grandfather: how, during the war, sand was dug from Hampstead Heath to fill sandbags, and when buildings were reduced to rubble by German bombs the rubble was deposited back in the pits from which the sand was dug. The city’s past is cannibalistic, a constant series of recyclings which infest the present.

It is in the present, in London circa 2000 AD, that Self is at his best. The grime of the contemporary city is phenomenally well-expressed. The London Show continues, in its two thousandth year at the same venue. The then rumbles seamlessly into the now, and Dave’s present is full of the knowledge of his city and its past.

The future reflects the past, and London’s auto-cannibalism continues, albeit somewhat distorted. Names become warped with repetition through the generations, and it seems that the real tragedy of the future inhabitants of Ham is their lack of a distinct past. Their history all stems from the book of Dave, and the reader’s awareness of its twisted psychoses exposes the flaws in any society’s dependence on a revealed religion or a single version of events. These people need more history, a second book to set the record straight.

So, history is powerful in this book. But by my reckoning, the present is the most intriguing part of the book. I initially wondered whether this could be labelled a failure in terms of dystopian literature, since the depicted future is not the most immediate part of the novel. On second thought, this seems like a very narrow reading. This is not a dystopia, but something much broader.

I think that our present is always likely to be the thing we can relate most closely to, particularly in a novel with such a sense of place. But I also think that our present, Dave’s present, acts as the conduit for the history and future which Self creates. Does that make sense? It is the focus. Dave’s actions, shaped by the past, shape the future which we are privileged enough to see running alongside the present.

I can’t articulate any of this as well as it is implicitly expressed in The Book of Dave. But this sense of deep time is one of the biggest things I took away from this novel.

Oh, and the storyline is ok as well.

Tuesday, 26 October 2010

Ubiquitous Cities

I read Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino a little while ago because I heard a few of my friends discussing it. Here are my thoughts.

The book is a fictional account of the travels of Marco Polo, as related by the traveller himself to Kublai Khan. His descriptions of various cities are interspersed with a dialogue with the Khan, in which it gradually becomes clear to the reader that all the cities described are really facets of a single city, Venice. I feel no compunction in spoiling this for you, because Vintage Classics, in their infinite wisdom, spoilt it for me by putting that morsel of information on the back cover.

Invisible Cities almost seems like a rough draft or a scrapbook full of ideas. Each city is unique, whether this is because of its unlikely location, bizarre architecture, or the characters and actions of its inhabitants. In one city, the citizens trail threads between themselves and all of their acquaintances, with different colours of thread symbolising different relationships; familial ties, business dealings, romantic entanglements. Finally, when there are so many threads that normal life becomes impossible, the inhabitants will abandon the city and move somewhere else, leaving their deserted, spider-webbed homes to be gradually destroyed by the elements. In another city, the residents build an exact replica of their metropolis underground in order to house the dead and make the transition from life to death less jarring. Or was it the dead who built the upper city?

Each city is a puzzling vignette, a glimpse of a different society and an entirely different way of going about one’s life. Many of them are very beautiful and thought provoking.

For me, it is precisely this that makes Invisible Cities so unsatisfying. Calvino dangles an idea in front of your eyes, and then whisks it away. Each city is given just a page or so. I’m sure the idea is to tantalise, but I found that the arrangement of the novel into single-page chapters was clunky and awkward, and many of the cities read like frustratingly abortive potential places. Somehow, they do not quite exist. Many of them cry out to be entire novels, beautiful and paradoxical ideas for societies that could be almost infinitely expanded. Why not do what Borges does, and take a philosophical trinket and stretch it to its logical conclusion? There are so many worlds that could be spun out from this book, but perhaps the elegance of these cities and ideas would be lost if they were used in this way. Their brevity and ambiguity certainly grants them a spell-like fascination.

My view of Invisible Cities is partly coloured by The Book of Dave, which I’ve nearly finished reading. Will Self calls London ‘the once and future city,’ and toys with the same kind of timelessness which Calvino does. London and Venice are both magical in the way they stretch away before and behind us, but I personally find the depth and saturation of Self’s 500-page vision of a city more enchanting than Calvino’s brief work.

This may be a little unfair though, since I’ve never been to Venice.

Friday, 22 October 2010

Back to Reality

I’m now about two-thirds of the way through The Book of Dave, despite the best efforts of the man on the train who kept almost falling asleep onto me. I’m really enjoying the book, and I would highly recommend it. Yes, it’s bleak and miserable, but it is also incredibly readable. The two parallel worlds reel you in, as each one gives you just a little more background on the other. It’s very well done.

As we witness the deranged cabbie, Dave Rudman, construct his own universe and system of beliefs, it becomes apparent just how fragile any such system is. One of my favourite words from the book’s bizarre vocabulary is ‘toyist’ – essentially it means that something is phoney or ersatz. Dave deploys this word regularly against anything he particularly dislikes, branding the subject false and invalid. This leads to intriguing clashes between the reader’s reality and the very persuasive reality which Will Self constructs. The humble pig, recognisable to us, is monstrous and ‘toyist’ to the inhabitants of the future island of Ham, because it cannot talk. Their livestock, in contrast, are initially grotesque but eventually endearing. They are the shambling, lisping motos which belong somewhere between a pig and a giant baby, and who vacuously but cheerfully greet their masters with an ‘orlri mayt’ even as they are being led to slaughter.

To the pig-farmers, the motos are vile and toyist beasts. To the inhabitants of Ham, the pigs are poor toyist copies of the motos, bereft of the power of speech. We should sympathise with the former, but we do not, because the novel works.

I’m sure this is all very poorly-explained and confusing. The main point I wanted to get at is that the word toyist is a well-executed, made-up word for something that we all do all of the time. It is a way of dismissing someone else’s reality if it does not accord with your own.

I’ve already started to adopt a few pieces of Self’s misanthropic vocabulary. It is impossible not to. The fragments of shattered glass from a car window are ‘ackney diamonds. A bloke who talks a load of rubbish has more f**king rabbit than Watership Down. In a similar vein to the adjective ‘toyist’, we see the invention of ‘chellish’ – that is, someone or something bearing a resemblance to Dave’s ex-wife Michelle, and being laden with all the bleak emotions that she evokes for our protagonist.

So, the creation of a vocabulary is a very powerful thing. It imprints Dave’s hate-filled psyche onto the reader, and it does it forcibly. Since we have only Dave’s words through which to understand the situation, we are forced to accept a landscape saturated with impotent rage. This is toyist, that is chellish, this is phoney, that is hateful.

In the same way that calling something toyist forces the namer’s perception of reality onto the named object, Dave’s inescapable vocabulary forces his twisted perceptions onto the reader.

Phew.

The Book of Dave does what I like in a novel, it plays with reality. And it does it very well.

Tuesday, 19 October 2010

The Traveller's Theory

I’m working on a theory, bear with me.

Travelling long distances over short periods of time is something that the human being is evolutionarily unprepared for. It’s like those hippies who say that drinking milk is bad for you, because it’s not natural to drink it apart from mother’s milk when you’re a baby, and your gut can’t cope. Evolution hasn’t caught up. I think this explains why travelling is always such an exhausting experience.

Somehow, some part of you realises that you’ve travelled a couple of hundred miles, even if it only took two hours. Some deep-rooted instinct knows that something quite remarkable has just happened. So, you become tired, grouchy, and feel compelled to purchase an overpriced hot water-based beverage from the buffet trolley. And of course, something else remarkable has happened, as it is difficult to tell what goes wrong in such a simple formula to produce a cup of scalding fluid that tastes... brown. But I digress.

There is a physical reaction to extended travel, and it doesn’t have to involve skipping timezones or anything complicated like that.

Admittedly, it does perhaps have something to do with the fact that you’ve just spent two hours staring out of the window and listening to Joy Division. Travel is a time for introspection. I enjoy the chance to do nothing but sit and listen to music or read a book, but it can encourage melancholy. Does mental languishing account for physical tiredness? Quite possibly.

The landscape doesn’t help, I think. I wonder if seeing so many things, flashing past, affects us. England from a carriage window is generally beautiful; you only need to read The Whitsun Weddings to know that. Even Yorkshire’s smoking stacks have something about them. Perhaps there’s a kind of sensory overload. We see quantities of things that, a couple of hundred years ago, it would have taken us weeks to see. Here is another city. Here are several hundred more people. Surely we should expect to be exhausted afterwards? Or are we already desensitised? I think not, because people-watching is always interesting, and trains are a good place for it. Seeing so many people and places is naturally exhausting.

Or perhaps it is because people are essentially conservative. With a very small ‘c’. They are, if not resistant to change, then at least affected by it in different ways. Or is that just me? Changing surroundings will result in changing moods, I think. When this is gradual, it is easy to deal with. When it is forcibly accelerated by the wonders of modern transport there is a gut reaction. It might not be as tiring as if you’d walked the whole way, but there’s definitely something there.

Thursday, 14 October 2010

Love and Hate in Hampstead

Another dystopian novel. Sorry about this. Normal service will be resumed soon.

This is certainly the most modern novel I’ve read for a while, Will Self’s The Book of Dave. It’s set in Hampstead in around 500 years time. In this future, rising sea levels have left the inhabitants of the island of Ham isolated from the other areas of high ground, visited only once a year for purposes that I don’t quite understand yet. Their religion and their entire society is based around a book written by a London cabbie from our time, named Dave Rudman.

This is a dense book. Self has created his own language in the Burgessian style, littered with Londonisms, cabbie slang and text-speak. The standard greeting of the inhabitants of Ham is ‘Ware2 guv?’ This makes for a lot of off-putting dialogue to be ploughed through. The first few pages were particularly difficult, but it doesn’t take long to get used to it. The strategy is just like reading Middle English; if you can’t decipher the word, reading it out loud normally helps. Eventually, this becomes good fun. It is enjoyable to be immersed in this bizarre vocabulary, to spot all the puns and references.

The same goes for the cosmos which Self constructs. Just like the vocabulary of the Hamsters (as the inhabitants of Ham are known), their ordering of universe is based around the book of Dave. Christianity is mercilessly parodied. Chronology is measured ‘in the Year of Our Dave,’ the omnipotent one can always see us through his rear-view mirror, and so on. The world of Ham is so sophisticated that the book even has a glossary at the back, but I always feel a bit like I’m cheating if I have a look in it. For the most part you can work out what he’s talking about, although it might pass you by at first. It reminds me of a grimy, mundane version of Eliot’s Wasteland, a system of allusions and references far too complicated for its own good. But somehow, Self manages to pull it off, I think because it is all very tongue-in-cheek.

Mentioning The Wasteland also reminds me of how London-centric this book is. I really enjoy this, but I wonder how much of the novel’s vitality would be lost on a non-Londoner. Self’s grubby view of London is devastatingly accurate, and perhaps unfamiliarity with the places in question would make it less interesting. I’ll have to lend the book around and ask for some opinions.

There is more than that, though. This book brings out the inherent irony of Hampstead. Let me try to explain what I mean. Like the Christian universe, the cosmos of Hampstead, and indeed the whole of North London, is ripe for parody. (I should point out that I lived in Gospel Oak during my formative years. Being situated between leafy, upper-middle-class Hampstead [only the estate agents call Gospel Oak ‘Hampstead’] and the ever-delightful Kentish Town lends a real variety to life...) North London is easy to parody because it is so middle class, darling. But I also think that many of its inhabitants are aware of this. It is a land of patisseries, boulangeries, and artisan bakeries. It is organic, it is free range. It is concerned with the poor, from the distance of the rich. Sometimes I love the place and sometimes I loathe it. But I certainly can’t afford it. And I think a lot of people feel this way.

By isolating Hampstead and cultivating his primitive society on its shores, Will Self pierces the façade and shows just how transparent it all is. He goes back to the bare earth of a place which actually has a remarkable and vibrant history. He uses it as his canvas, reshaping much of it, but keeping just enough intact to anchor his novel in reality and provide a generous serving of in-jokes. Whether or not these are funny to anyone else is a good question.

Sunday, 10 October 2010

The Man in the High Castle

I want to write about this book, but I need to return it to the friend who lent it to me and who hasn’t had a chance to read it. So this might be a little bit tricky.

About halfway through The Man in the High Castle, I thought Philip K. Dick had a slightly irritating awareness of just how clever he was being. The man in the novel’s title is an author who writes a book which is, in the world of the novel, immensely popular. The book, called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, is about what would have happened if the allies had won WWII. I know, crazy, right? Philip K. Dick’s characters seem to spend a lot of their time fawning over how clever the author was to think of such an impressive vision of an alternative world, with the clear implication that Dick’s own book is wonderful.

Without wishing to spoil it, the book within the book is very important. This is revealed with an irritating lack of subtlety. One character is troubled by the fact that the alternate world of the author, a man named Abendsen, is ‘somehow grander, more in the old spirit than the actual world.’ Later on, a different character meditates on the relevance of the novel within the novel: ‘He told us about our own world... This, what’s around us now.’

Of course, this is the mark of a good sci-fi book. (I don’t think it can really be called a dystopia, as it takes place in an alternative present, when the book was written in the 60s, rather than an alternate future.) It tells us about the society which produced it as much as the fictional society which it creates. But surely this doesn’t have to be directly observed by a character in the novel for the reader to notice it?

Despite this sledgehammer approach, the book is good fun. I always really enjoy an author who plays with the boundaries between truth and fiction, between various different layers of reality. Dick certainly manages that, and there are elements of subtlety. The book’s subplot features the forgery of historical and cultural artefacts, before the characters who do the forging become original artisans in their own right, creating beautiful and unique jewellery. Reality and artifice flow throughout the book, and the relationship between the two is highly ambiguous. Many things are not as they seem, helping to create a classic atmosphere of paranoia.

One of my favourite lines relates to this. There is a discussion, at one point, about how the historicity of an artefact is what creates the item’s value. The forgery was not there, at that time, when that event happened. Although it is identical in every other way, it lacks this authenticity which is provided by its historical circumstances. One character shoots a couple of people dead, and watches horrified as their blood pools on the floor. Even when it is all cleared away, and no visible sign remains, he is aware of the ‘historicity’ bonded into the nylon tiles on the floor.

So, this is the division between truth and reality. Inanimate objects are witnesses to various atrocities, whether in the alternate present of the The Man in the High Castle or the alternate-alternate present of The Grashopper Lies Heavy... which should therefore be the actual present. Or something. Very little is objectively verifiable. What is clear is that you can’t trust what people say, and you certainly can’t trust what they write.

Thursday, 7 October 2010

The Don Rides Forth

Such an exhumation will never be dignified. The Don rides forth, strapped to his trusty steed like the Cid, and just as incongruous.

Monday, 4 October 2010

Finishing and Starting

Finished One Hundred Years of Solitude yesterday. Ironically, about a page and a half before the end, an old neighbour of ours came over and stayed for a twenty minute chat, thereby utterly derailing my train of thought.

I eventually resolved my problem and decided that I like the book. To me it seems to follow the same pattern as Kafka’s Trial. Initially, it is enchanting, mesmerising, it reels you in. This is followed by a tedious midsection, caused by a lack of activity, and in Marquez’s case I think it is also arduous because of the oppressive solitude and misery which he conjures so effectively. Ultimately, both books end with catharsis, but I won’t say more than that.

Next on the list is a book lent to me by a friend with an interest in dystopian literature. It is Philip K. Dick’s 1962 masterpiece, The Man in the High Castle. I’m not really a sci-fi fan, despite my fondness for Red Dwarf and the Hitchhiker’s Guide, but I think this is mostly due to snobbery. There is an interesting question as to where exactly science fiction and dystopian “literature” overlap. Someone like Huxley clearly belongs in the latter category. I’m intending to re-read Brave New World soon, as it has faded from my memory remarkably effectively. I am a literary snob, and I like to feel that I’ve got something out of a book at the end of it. We’ll see if this happens with Dick’s book, and that will be the outrageously subjective basis for my categorisation of it.

I don’t have a lot to say about The Man in the High Castle just yet, as I’m only around sixty pages in. It is a vision of post-WWII America following the victory of the Nazis and the Japanese. Dick’s main concerns so far are the logical yet dizzying conclusions of Nazi racialism and eugenics. The whole of Africa has been wiped out in a grotesque experiment. Relations are defined by race, with the few remaining blacks and Jews at the bottom of the pile, and the Aryans and Japanese uneasily coexisting at the top, now rival powers on the opposite seaboards of the former United States. The mongrel Americans (my choice of adjective, and before anyone gets upset I believe it is both flattering and accurate) tip-toe around, desperately kow-towing to their new masters, whilst denigrating those below them in accordance with the esoteric rules of a culture wholly alien to them. Once more we return to Kafka. As with all good dystopian visions, paranoia is everywhere.

So far, so unremarkable. But I know I’m being unfair.

There are always dangers in reading a classic of dystopian literature almost half a century after it was first published. Some of them age gracefully, and others do not. Dick seems to have done fairly well. The what-if-the-Nazis-had-won scenario still holds a terror for Europe and America, I think, since it is impossible to look back on such a period of bloodshed without wondering what could have happened. On the other hand, it does seem to be a fairly easy recipe for creating a story: take what might have happened, and stretch it to its logical conclusion. This is one root of many dystopian visions, although it would be unfair to paint the author as a mere follower when, fifty years ago, he was a trailblazer. Hopefully, Dick has not become a victim of his own success in the way that other visions of the future have, becoming trite because of their incredible popularity.

While I read the book, I’ll have to keep reminding myself that he got there before a lot of others did, and I’ll wait and see whether The Man in the High Castle yields something special along the way. HuHu

Friday, 1 October 2010

More on Marquez

I still can’t quite make up my mind about One Hundred Years of Solitude. I really enjoyed it to begin with, then went off it, and now I like it again. I think the problem for me is that Marquez’s characters are so fundamentally unlikeable, but his descriptive writing is so good that he achieves an awkward ambivalence, at least for me.

The Buendia family is a parade of grotesques. From the mad Jose Arcadio Buendia, tied gibbering beneath a chestnut tree, to the seemingly immortal Colonel Aureliano Buendia, whose guerrilla campaign is both tragedy and farce. Reports of his death were greatly exaggerated, and even his own attempt at suicide was a failure because his doctor predicted it and gave the colonel false information when he asked precisely where his heart was. These characters appear in the first half of the book. They are roguish and have their own charm; they are romantics, explorers, adventurers.

I am currently in the middle of the book, and the later generations of Buendias do not, for me, have the same charm. Many of them are dominated by their own fleshly pursuits, chasing women old enough to be their mothers, or women who are in fact their half-sisters or aunts. I’m not a prude, but it gives me a little British shudder.

The book is unquestionably visceral, and this comes through in the musty, sweaty sex scenes. It is also manifested in the periodic outbursts of bloody violence, the daughter who eats earth and whitewash from the walls when she is upset, and the suffocating closeness of the village of Macondo, in seeming isolation from the rest of the world. It is a dirty place, and it is testament to Marquez’s evocative style that the characters and their vices are so repellent to the reader.

I find myself willing forward the conviction of the matriarch, Ursula, that one day the family will have a Good Son who will be a priest. But since the previous priest had an unusual fondness for female donkeys, even this idea seems tainted. She begins to be superstitious that the family’s run of ne’er-do-wells is a result of the reuse of names, and she rows with the younger generations over the proposed names of their offspring. This too, is a conviction that the reader shares. Despite the family tree at the beginning of the book, it is virtually impossible to keep track of all the Jose Arcadios, the Aurielianos, the Aureliano Joses, the Amarantas, the Rebecas, the Remidioses.

Eventually – and for me this came only about a third of the way through the book - they coalesce into a repulsive tangle of dirty habits which is not easily resolved. They procreate, and the same names and the same vices become perpetual. This, of course, is the point of the book. It is a catalogue of misfortune that spans so many generations that one all but loses track, lost in the rottenness of the family and the village. We become irrevocably involved.

I’m not a sucker for a happy ending, but I hope there is a priest, and I hope he turns out alright.