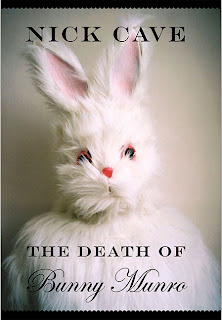

Don’t get me wrong, I really like Nick Cave’s music. I just don’t think he’s quite managed to become a novelist yet. His first novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel, was published around twenty years ago, and was so self-consciously verbose and writerly that when I read it I spent half of my time reaching for the dictionary. He has mercifully overcome this tendency with his more recent work, The Death of Bunny Munro.

Unfortunately, that is one of the book’s few redeeming features. Here is my main problem with it: it is utterly obscene. I’m not a particularly prudish person, but there was just too much sex and swearing in there. And more to the point, it seemed to me that the near-constant sex in Bunny Munro did virtually nothing for the plot. Ok, Bunny is clearly a sex addict and that is an important part of the story, but that was successfully established after a couple of lurid chapters. Is it really necessary to reiterate it in every other paragraph?

Obviously I can’t go into too much detail because my mother reads this blog (Hi Mum!) but you’d be amazed at how many times the word ‘tumescent’ um, came up in this novel.

So, any other problems? Well, it was also a massively over-hyped novel. I suppose this is fairly inevitable with a ‘celebrity’ author, but the reviews were fawning and I’m inclined to think that the book’s status as a bestseller is due to the legions of fans of Cave’s music. People, in fact, just like me. Fortunately my brother bought me this book for Christmas, so I dodged a bullet there.

So, any other problems? Well, it was also a massively over-hyped novel. I suppose this is fairly inevitable with a ‘celebrity’ author, but the reviews were fawning and I’m inclined to think that the book’s status as a bestseller is due to the legions of fans of Cave’s music. People, in fact, just like me. Fortunately my brother bought me this book for Christmas, so I dodged a bullet there.

There are times in the novel when Cave the songwriter makes himself known, and these provide some welcome relief. Bunny’s redemption scene – which incidentally appears out of nowhere in terms of plot – is written with the kind of Old Testament richness for which Cave is rightly known. This was what he excelled at in his previous novel, discussing evil, damnation and salvation in heavy tones that call to mind William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, and the whole Southern Gothic gang. Sweating buckets of blood under the hot red stagelights, Bunny asks forgiveness from all those he has wronged. In my view, it’s an ending that redeems the novel as a whole, not just the protagonist.

Other enjoyable aspects include the misguided sense of hero-worship that Bunny Junior has for his father. The relationship between them is tender, and Bunny clearly does care for his son, but this becomes irritating as Bunny’s catalogue of disgraceful acts continues to grow and his son’s attitude doesn’t change. Of course, it’s better to be irritated by an author than completely unmoved, and Bunny Junior is very useful as a sympathetic character without whom the novel would be, well, fairly unlikeable.

So, Cave the novelist is almost there. He was overeducated and tried too hard in his first novel and is lewd and crude for no particular purpose in his second. What he has always done well is misery and transgression, but I think he has yet to pitch it as well in a novel as he does in song.

And my other piece of advice, Nick, just for the record, is to lose the moustache.