A quasi-literary blog: book reviews in modern and classic fiction, occasional original stories and frequent pontification. Come on in.

- For Whom the Bell Tolls

Monday, 28 November 2011

Trouble in Wayne County

Wednesday, 17 August 2011

Tales from the Churchyard

Monday, 25 April 2011

Doppelgangers, Golems and Hermaphrodites

Sunday, 3 April 2011

A Very British Whodunnit...

Monday, 28 March 2011

Horrors Manufactured Here

Saturday, 19 March 2011

Books Burn Badly

Wednesday, 9 March 2011

A Novelist of the Floating World

Tuesday, 1 March 2011

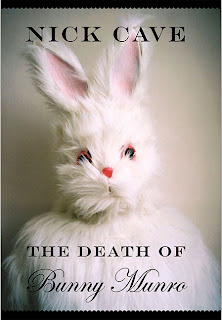

Caught in the Headlights

So, any other problems? Well, it was also a massively over-hyped novel. I suppose this is fairly inevitable with a ‘celebrity’ author, but the reviews were fawning and I’m inclined to think that the book’s status as a bestseller is due to the legions of fans of Cave’s music. People, in fact, just like me. Fortunately my brother bought me this book for Christmas, so I dodged a bullet there.

So, any other problems? Well, it was also a massively over-hyped novel. I suppose this is fairly inevitable with a ‘celebrity’ author, but the reviews were fawning and I’m inclined to think that the book’s status as a bestseller is due to the legions of fans of Cave’s music. People, in fact, just like me. Fortunately my brother bought me this book for Christmas, so I dodged a bullet there.Thursday, 24 February 2011

Yossarian Strikes Again

Thursday, 17 February 2011

How to write when you just don't want to

I don’t care what anyone says, non-fiction is easy. Without an idea, you cannot write fiction. Without a clue, you can still write non-fiction.

I don’t care what anyone says, non-fiction is easy. Without an idea, you cannot write fiction. Without a clue, you can still write non-fiction.Tuesday, 8 February 2011

Gone Fishin'

Monday, 31 January 2011

Something Amis*

Wednesday, 26 January 2011

Fiction for the Unemployed: my five favourite charity bookstore bargains

- Cervantes – Don Quixote

- Umberto Eco – Baudolino

- Martin Amis – London Fields

- Anthony Burgess – The Devil’s Mode

- Italo Calvino – Invisible Cities

Wednesday, 19 January 2011

Damned Lies II

Friday, 14 January 2011

Lies, damned lies, and medieval history

Thursday, 6 January 2011

Daisy, Daisy...

The first time I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey in the cinema, I was about fourteen years old, and it meant absolutely nothing to me. Worse than that, in fact, it was downright boring. Then I saw it on TV a couple of years ago, and I really enjoyed it. Now I’ve finally got around to reading the book.

It was written by Arthur C. Clarke and based around the screenplay which he and Stanley Kubrick created. Relationships between films and books are always tricky (I had similar concerns about reading The Warriors), and normally a book derived from a film sets alarm bells ringing, but I had heard only good things about 2001.

The first thing to say about this novel is how it massively helps you to understand the film. Because the film has no omnipresent narrator, there is no way for the audience to understand the incredible things that are going on. The novel explains what is actually happening, what the monolith is doing, what all those multi-coloured swirly things are meant to represent. In this respect, it almost seems like a crib sheet or a set of Sparknotes for the film.

Of course, this is a gross injustice. I’d never actually read any Clarke before, but he writes very engagingly, and with just the right ratio of science-to-fiction. There was a seasoning of occult astrophysics which allowed all sorts of bizarre things to happen, but there was never enough to be alienating to a sci-fi toe-dipper. Unlike some authors in the genre, Clarke doesn’t get too bogged down in how and why things happen, he just lets them. The fiction is the important part.

More or less everyone knows something of the storyline, the Hal 9000 computer who turns renegade millions of miles from earth and kills most of the crew of the Discovery. I found that knowing the plot created a real sense of impending doom, particularly when we first begin to witness Hal’s slow deterioration, described in very human terms of growing self-doubt. The scene where astronaut Dave Bowman finally unplugs Hal is hugely moving and rightly famous. It is also very easy to be affected by the incredible isolation forced upon Bowman himself. With his companions gone and the computer offline, he is left alone on the Discovery, drifting along the ship’s predetermined route, from which there was never intended to be any return and there is now little hope of rescue. Of all the entertainments on board the ship, it is Bach’s cantatas that offer Bowman the greatest solace.

The most remarkable part of 2001 is the part which makes least sense in the film; the journey through the monolith. Bowman is swept along, shielded by unseen powers from temperatures and pressures that should have crushed his fragile, man-made vehicle. And eventually, well, even the parts with the hotel room and the giant baby more or less make sense. From his tremendous and powerless isolation, the protagonist (he is no longer ‘Dave Bowman’) emerges as... something else. Something of limitless power and potential, to which the troubled, warlike earth of the twenty-first century is utterly insignificant.

2001 is a short but powerful novel that effortlessly spans several millennia. It sees mankind go from cowering apes to weapon-wielding hunters, and from stone axes to the brink of nuclear war. Clarke bends time and scale to his narrative, and creates what is generally an absorbing and convincing fiction, with human tragedy and eventual catharsis. 2001 is a long way from a pulp fiction movie tie-in.

.jpg)